“As a research scholar and an expert on the subject of gladiators and amphitheatre spectacles in general, I have always considered regrettable that the cinema, TV, literature, and videogames do not usually offer an accurate image, faithful to the historical truth, of gladiators and their world, of what they were really like. There are aberrations in many aspects. The first aspect where we may notice an inaccurate way of representing gladiators is in the equipment, the weapons and the clothes they wore. We often see gladiators without helmets, or wearing a cuirass or breastplate, or with footwear, whereas in fact, the majority of the gladiator types wore helmets, did not use a cuirass (they fought bare-breasted) and went barefoot. In general, they are shown with fantastic armour that is not at all like the armour they really used and, in those cases where the pieces of armour are accurate, they are wrongly combined: to give high greaves to a gladiator who uses a scutum is a common mistake.

Other mistakes that we often see are the use of the thumb gesture, up or down: these are gestures that were never used by the Romans; the “Ave caesar morituri te salutant” salute, words that were never pronounced by any gladiator; or the presentation of gladiators fighting against animals, when gladiators never fought against animals, only against other gladiators.

As conducted a research into the profession of gladiator, I often thought how easy it would have been for all those movies, TV series, books and videogames to show an accurate image of gladiators; they would only have needed to seek the right advice. I began to doubt whether any of the people who had created those works cared the least about historical accuracy. It came, therefore, as a pleasant surprise to me when, in February 2014, David Temprano contacted me to say that he was developing a board game about gladiators, to be called ‘Gladiatoris’, and that he wanted to have correct historical advice. As a researcher on the subject of gladiators, it is one of my ‘duties’ to disseminate knowledge of it, and a board game seemed to me an ideal means to spread the word about the world of gladiators among the general public. It also seemed to me a great opportunity to put all the above-mentioned mistakes behind us. They are often apparent in the board games about gladiators that already exist, so we could at last create a board game that is accurate as regards the appearance of real gladiators in ancient Rome, and in terms of the whole historical context in which their fights took place.

With that goal in mind, David and I started work.

Gladiator sports have existed for over eight centuries. Obviously, it is such a long period that it saw many changes, such as changes in the equipment, so the first thing to do was to decide which moment of the history of the gladiator we wanted to show in the game, with the purpose of endowing all our gladiators with the proper equipment of that historical moment, thus avoiding mixing gladiators with equipment of different periods, another common mistake. I chose the first century AD, which can be considered the Golden Age of gladiator sport. Hence, for example, among other details, all the gladiators in the game wear helmets that cover their face, because the helmets that left the face exposed were only used during the Republic. After the Reform of Augustus, all the gladiator types that wore a helmet changed to the compulsory use of helmets that covered the face.

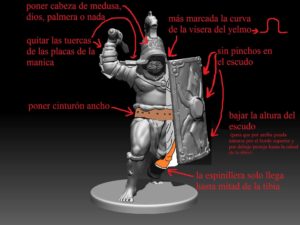

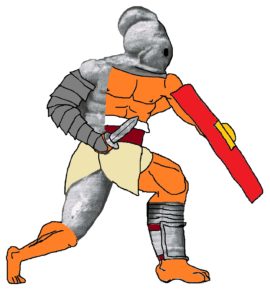

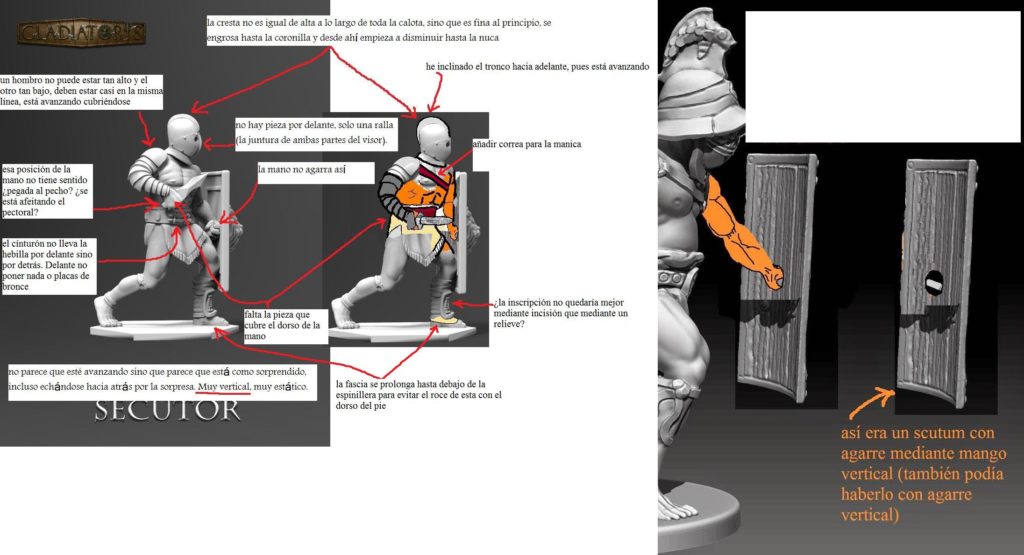

Essentially, each one of the miniature figures in the game has been created from Roman sources. For example, the miniature of the secutor is based on Roman visual sources of secutores, and on pieces of secutor armour found in archaeological excavations, such as the helmets discovered in Pompeii. We worked in the following way: I sent a drawing and photos of the real sources to the sculptors, and they reproduced them in the corresponding miniatures. The meticulousness of this process can be seen to its full extent in the pages that David has devoted to each gladiator on this web and in the blog.

Thus, we have managed to create miniatures that are accurate according to the original models from Roman times that have inspired them, and with regard to this, I would like to stress especially the helmet of the secutor, as it is identical to the original helmet from Pompeii that was its model. The helmets of the thraex and the provocator are also virtually identical to their models from Pompeii, the only difference being that we have added the animal of the corresponding gladiator team to which those two gladiators belong in the game: the panther and the wolf, respectively.

In fact, those elements that have been added due to the logic or rules of the game are the only elements that differentiate the miniatures from their models from Roman times. Otherwise, the greaves, manicae, belts, and other items of equipment are identical to those of Roman times.

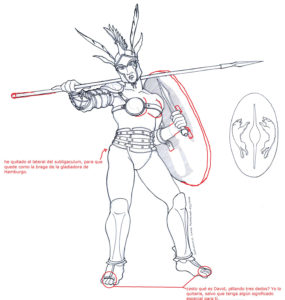

Those elements added according to the requirements of the logic of the game are mainly the animal symbols of each team, as we saw. Each team has its own animal symbol or symbols: the lion and the hyena are the animals of the red team, the wolf that of the green, the leopard that of the blue, and the tiger and the snake those of the orange team. These symbols obviously do not appear on the original pieces of armour of Roman gladiators. However, we made sure that the addition of the symbols is plausible and credible, and that they do not clash with the Roman sources. In fact, the Roman sources bear similar motifs in bas-relief, for example, the helmets of thraeces show dolphins, the galeri [shoulder-piece] of the retiarii display tridents, crabs and dolphins, and the heads of mythological beings often feature on the cardiophylakes [breast-plate] of provocatores and on the shield of equites.

In the same way, due to the logic of the game, the dimachaerus has been assigned to the team of the miniatures without a helmet, so he is represented without one, although real dimachaeri probably fought with a helmet. In real gladiator sports, the retiarius was the only gladiator type who fought without a helmet. In any case, no Roman source shows a dimachaerus in an incontrovertible way, so since we do not know exactly what that gladiator looked like, we have allowed ourselves a certain licence with him.

Apart from the gladiators, the rest of the miniatures of the game, such as slaves and animals, have also been designed from Roman sources. The level of detail with regard to this has been notable too: for example, the slaves wear a chain around their necks with a medallion that is inscribed in Latin, an almost exact replica of a real slave medallion. Chains, handcuffs, swords and the rest of the objects have equally been modelled on their real Roman counterparts. The animals have also been designed from Roman sources depicting those animals, mainly sculptures, frescoes and mosaics. We were not so much interested in creating a miniature of a real lion as in creating a miniature that looked like a genuine Roman lion, with the look and aesthetics of Roman art. We think it helps to give the game the ‘Roman flavour’ we want it to have.

Also, in order to enhance that Roman flavour, historical accuracy has been applied to all the elements of the game where it was possible, thus, for example, gladiator types are referred to by their original Latin names, with the singular and the plural, e.g. retiarius and retiarii, provocator and provocatores, and so on. Even the name of the game itself is a real Latin word: Gladiatoris, the genitive singular of gladiator, which translates as “gladiator’s”, something pertaining to a gladiator. Certainly, the name expresses perfectly what we wanted to create, a game that in its subject matter as well as in its aesthetics, a gladiator could see as something familiar to him, something of his own, a game that the ancient Romans could have seen as an activity carried out by a gladiator. Nothing gives us more satisfaction than to think that we have managed to create a game that the gladiators of ancient Rome would have enjoyed, and they would have played it in the breaks between their combats and training sessions, in the same way that they played dice and knucklebones.

Since we obviously cannot express in the game all the aspects of the world of the gladiators, the game is accompanied by a glossary (revised by me), where I explain, briefly and in terms that can be understood by the public at large, the different elements that made up gladiator sports (gladiator types, weapons, vocabulary of the arena, etc.). Any player interested in deepening her/his knowledge about the world of the gladiator can do so by reading my book Gladiadores: el gran espectáculo de Roma.”

Alfonso Mañas

Alfonso Manas holds a PhD (with European Mention) in the History of Sport from the University of Granada, Spain. His PhD thesis dealt with gladiators (Munera Gladiatoria: Origin of Mass Spectacle Sport). He has published several academic articles on the subject, and he is the author of the book Gladiadores: el gran espectáculo de Roma (Ariel, Barcelona, 2013).

Alfonso Manas has also revised the extensive glossary that accompanies the Gladiators Book of GLADIATORIS. There you will find the definition of many Latin terms connected to the arena, gladiator types, weapons, items of equipment, rituals and customs of the arena, gods and festivities… several of the games in the Games Book have been designed from that information.